Want to put a cap on a character in a scene? Make it rain—or better, make the sun shine? Give the protagonist the face of a famous actor or a sorrowful expression? Have them deliver precise lines, hide their eyes behind dark glasses, change the camera angle, or dress them in nineteenth-century clothes? In just moments, as if by magic, the scene takes shape according to our instructions.

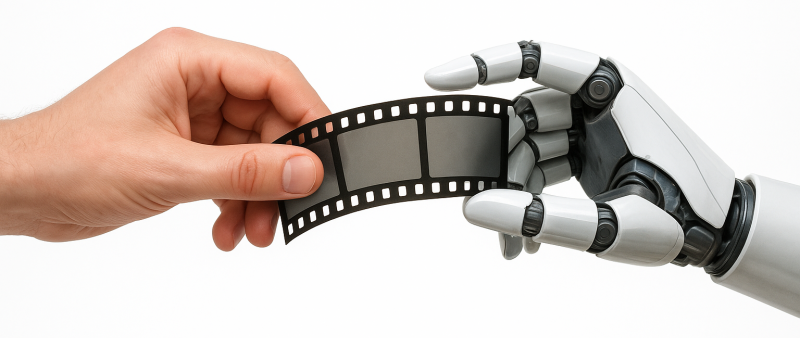

Despite the tendency to humanise them, AIs are not individuals. They are programs—mathematical and computational models—which, when loaded onto computers equipped with increasingly powerful (and prohibitively expensive) graphics cards and processors, are capable of performing an extraordinary number of calculations, altering the data we provide or generating new material from our prompts. In the worlds of cinema and computer graphics, they should be regarded as “advanced tools,” not sentient entities with a consciousness of their own.

Even so, the use of artificial intelligence in film production has caused consternation. The situation seems paradoxical: even actors themselves feel threatened and fear for the future of their profession. AI streamlines visual effects and upends technical processes that experienced operators have long been accustomed to.

Yet the same thing happened with the arrival of digital technology and computer graphics.

Today, tools exist that can recreate certain effects or scenes with far less time, fewer resources, and fewer people. One mustn’t forget that cinema itself is a child of technology—and that the first cinematographs were not well received by those who worked in theatre or wrote novels.

A degree of apprehension is therefore understandable, but in truth, it has always been this way: cinematic techniques evolve over time.

Indeed, there are already several AI models, some open source and others proprietary, capable of generating characters, voices and scenes with a consistency that until yesterday seemed unthinkable. Online platforms such as Openart.ai, Runway.ai, Fal.ai and Huggingface.co provide generative AI tools with astonishing abilities. Examples include Runway Gen-4, Google Veo 3, OpenAI Sora, Luma Labs’ Dream Machine and Kling AI 2.0, which allow the creation of high-quality videos at lower cost and in less time—tasks that until very recently would have required a complex mix of techniques and highly specialised professionals.

But this is not only about speeding up processes or cutting costs—it is also about opening new creative possibilities. CGI had already achieved such a degree of photorealism that it could replace actors and sets, and yet audiences continue to crave genuine emotions, familiar faces, and the magic of the encounter between the real and the imagined.

Cinema has always undergone radical transformations: from silent to sound, from black and white to colour, to computer graphics, 3D screenings and 4D cinemas. Each time, people feared the end of an era—and each time, cinema discovered new forms of language and spectacle. The advent of artificial intelligence marks yet another step in this ongoing evolution.

Cinema has never stood still: it has extended onto the web in endless series, become a stream of chapters and intricate narrative universes, produced ever more quickly. AI enters into this evolution not as a replacement, but as an upgrade: an accelerator that unleashes creative energy and opens the way to hybrid forms still waiting to be invented.

Author: Emanuele Mulas, M.Sc. MIEI

----------------------------------------------------